Bridgeville Memories

by Koder Collison

History fades into fable and fact becomes clouded with doubt and controversy... Washington Irving

Bridgeville two hundred years ago? I don’t know. I’ll leave it to the historians diligently searching the archives to determine the birthdate of its establishment.

True, as far back as 1631, the Dutch established a settlement—Zwaanendael—in the Lewes area, which was wiped out by Indian massacre a year later. As a result, it may be said that the first permanent settlement did not come about until 1638, when the Swedes established Fort Christina, now named Wilmington. But little development was occurring in the hinderlands of lower Delaware.

A brief history of Seaford, eight miles to the south of Bridgeville, opens with this statement: “The history of Seaford may safely be said to have commenced with the dawn of the 19th century. Imagine a few isolated buildings in a clearing by a river and you have a picture of this village circa 1790.”

The layout of that community was not completed until 1799 and the first store was established in 1800. Since Seaford had the advantage of the Nanticoke River which afforded access for relatively large vessels plying the waters to and from Chesapeake Bay, it would seem to me that Seaford may had had the march on our town of Bridgeville.

Whether or not my view is loaded with logic seems of little consequence when consideration is given to the opportunity we all have to celebrate the birth of our great nation. It is a time to return to love of country, respect for traditional values, and confidence in the future.

The Bridgeville I am discussing is the community I knew so well a half century ago. Friendliness prevailed. The only divisiveness among our people came on the sundry election days and even that was greatly tempered with good-natured banter between representatives of the two major parties.

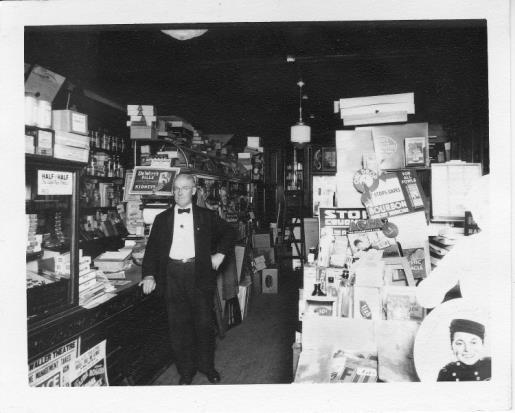

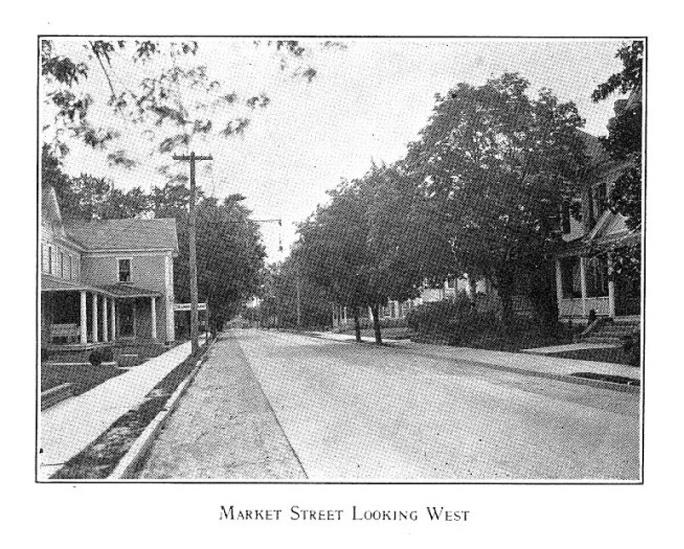

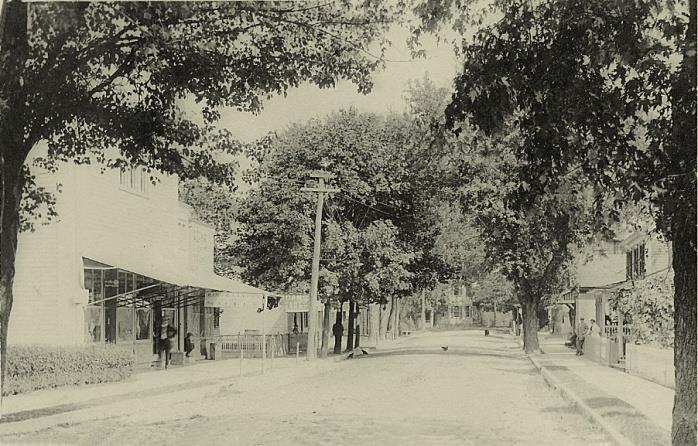

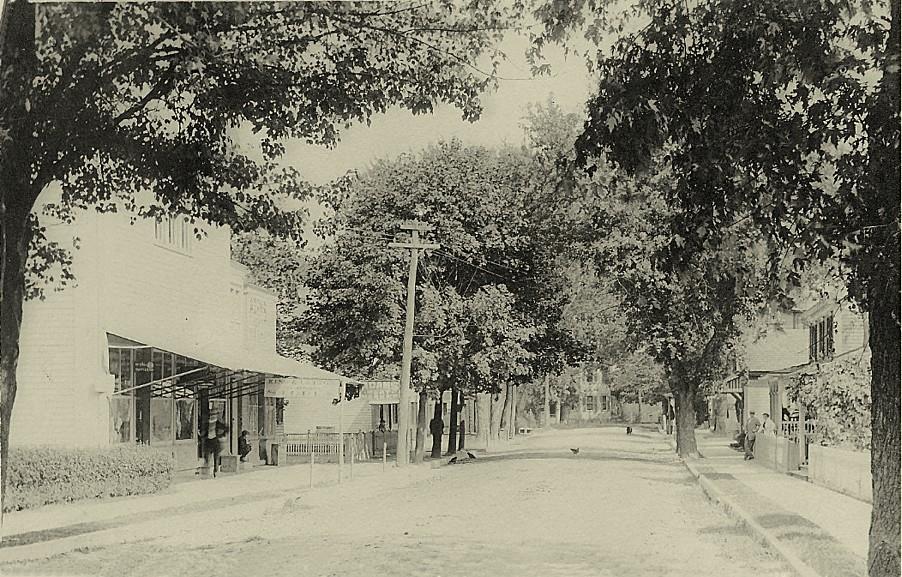

More about that later on. Meanwhile let’s take a bit of a tour along some of Bridgeville’s business district of the late ‘teen and early twenties.’ The Delaware Railroad (later a division of the Pennsylvania) had been extended to Bridgeville from Dover in the latter 1850’s and completed to Delmar by the close of the decade.

By 1920, the railroad offered through service from New York to Cape Charles with ferry connection to Norfolk, and the little red depot at Bridgeville was doing a big passenger business destined both north and south as there were four daily trains scheduled in both directions.

Almost directly across from the station was the two-story Bridgeville Hotel with comfortable rooms and excellent food. Drummers (salesmen) prior to the popularity of the automobile would arrive at Bridgeville by train and register at the hotel. They would hire horse and buggy at a local livery stable and make forays in to the farm country during the day but return to the hostelry for the night. Calls on foot were made to the local stores and other retail and wholesale outlets, but twilight would find the vendors back at the hotel for a sumptuous meal, many times followed by poker with fellow travelers.

True or not, I do not know, but I have been told that, on more than one occasion, certain salesmen had to leave their sample with the innkeeper as security for room rent, after having participated in the card games.

But no matter, as they had return passage on the P. R. R. and would be back in town later to reclaim their baggage and such.

As one stepped off the veranda of the hotel and headed north along Railroad Avenue, he would come to an unusual store. It appeared to be a grocery, or general store, but was really more. It boasted a soda fountain and tobacco stand as well as a number of tables in the rear where one could get a sandwich or plate of baked beans. There had been previous owners, but in the early ‘twenties,’ its sign Bradford P. Jones was in a number of businesses including purchase, sale, and shipment of mine props which he and my uncle Norman purchased in various areas on the Peninsula.

But B. P. enjoyed the store, and from time to time, permitted me to work behind the soda fountain, a real treat for a twelve-year-old.

That property, along with some neighboring lots, is now occupied by RAPA Brand products (since 1926.)

Photo courtesy of Michael V. Layton

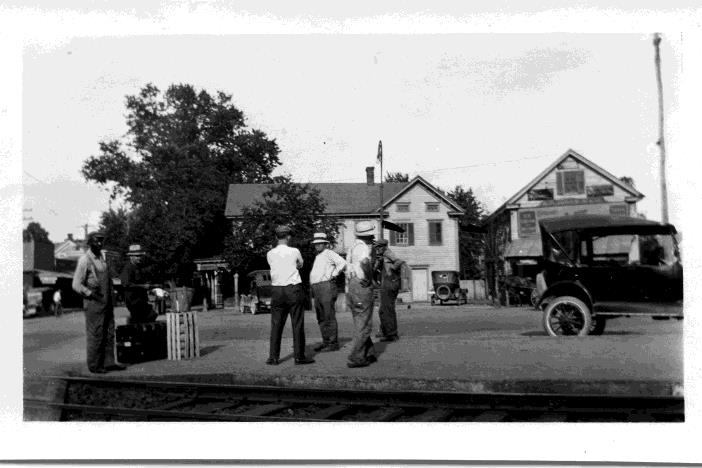

On the corner of Railroad Avenue and Market was Ed Elliott’s Drug Store. Here it was that some of the farmers and local businessmen gathered to discuss the problems of the day. A long bench was situated along the store front and the area would become befogged with tobacco smoke as the clan gathered to argue politics and sports and, until the election of 1928, there were no religious discussions.

The inside of the store made one wonder how inventory could even be taken if it ever was. Tobacco products intermingled with patent medicines, notions, novelties and other ware of usual and unusual nature.

One thing, though. Ed Elliott never had any problem finding the products ordered by his customers and “clients” as he sometimes called the hangers-on.

We turn the corner and head east on Market Street. Next to Ed Elliott’s store and home was Ed Adams’s meat market and butcher shop. Here was the birth of RAPA Brand dreamed up by Ralph and Paul Adams who learned the secret formula for that delectable scrapple now sold all over the eastern United States. They decided to branch out, bought two Model T Ford panel trucks, numbered them 11 and 12 and raced up and down the highways and by-ways until potential customers got the idea they were doing a Big business. And soon they were.

The new brick production plant was built and Ed Adams’s old store became a barber shop where Frank and Oscar Rickards clipped hair, shaved faces and necks, and told funny (and unbelievable) stories.

A home or two separated the Barbershop from Bridgeville’s first chain grocery—the American Stores Co., presided over by Harry Ake. Once, a fellow named Kimbrow from down Salisbury way, came to work for Mr. Ake and conned one of my more gullible female cousins into believing he was assigned to spy on Harry’s store operations. Mr. K. soon left, but not before he operated a one-man cleaning establishment next door.

Two stores which continue to operate today much as they did a half century ago, face each other across Market Street. One, the Layton Hardware store. I’ll get to that later.

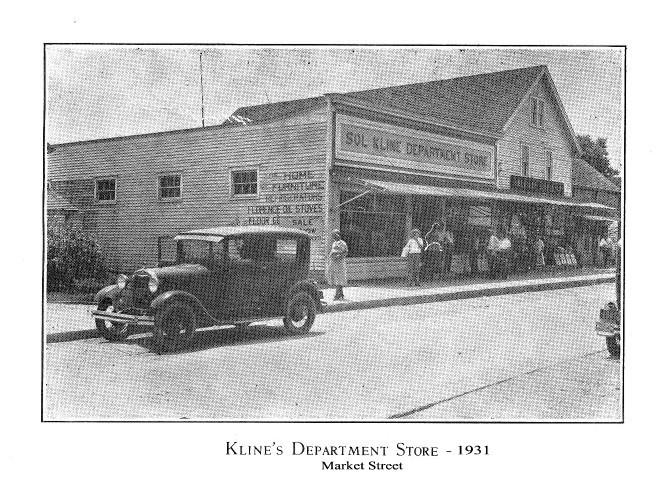

The Sol Kline Department Store was truly a modern day emporium even back in those late ‘teens and ‘twenties. First class, name brand, merchandise was available; ready-made dresses as well as bolt goods could be purchased along with notions and costume jewelry, handbags, shoes, and what have you. Curleyheaded Sol Kline was a joy. Always smiling, he had a kind word for all, regardless of their economic standing.

Hattie Kline, his younger daughter, went to Bridgeville school during my time. Bessie, his elder, red-headed daughter, attended Goucher College, as I believe Hattie did in later years.

Luther Calhoun’s family resided in a home set back from the street neighboring the Kline store. Luther had a barbershop also. It was unusual in some respects and that, too, will be discussed later in this writing.

Photo courtesy of Michael V. Layton

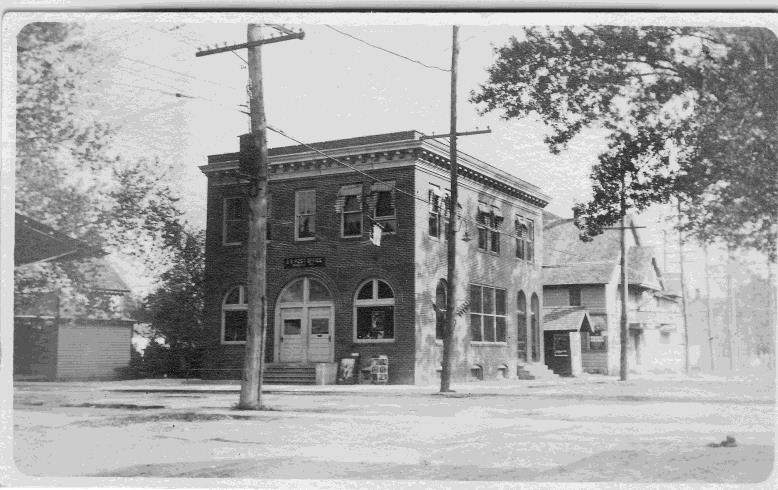

Further east on the south side of Market Street was the U. S. Post Office; the building now occupied by the Bridgeville Fire Department.

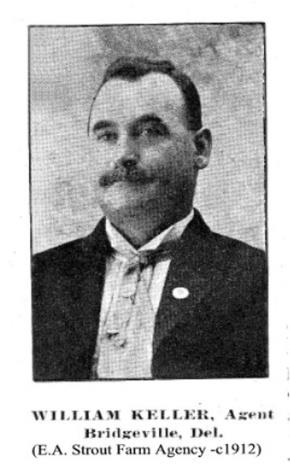

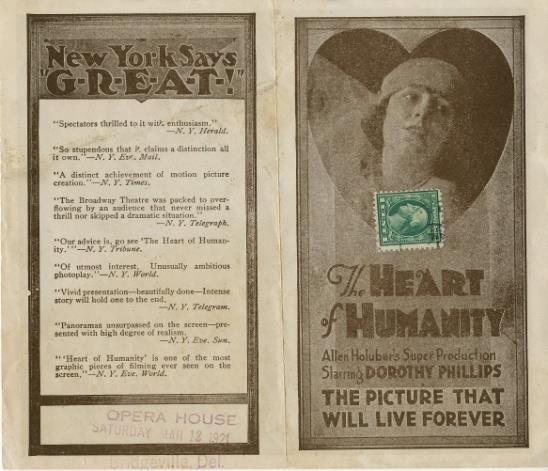

Along with recruiting posters gracing the sidewalks in front of the building, were also posters (enclosed in chicken wire framework) announcing the pictures to be shown on Wednesday and Saturday nights at Keller’s Theatre located to the rear, and beyond the post office. Here it was that we swains would hold hands with those we thought were our best girls.

Actually, the girls would pay their ways in prior to us coming on the scene. They would sit in one row and us in the row directly in front of them. As the picture started, and the lights went out, we’d reach over the back of the seat and “play hands.” This sometimes resulted in a crick in the neck or shoulder because of the length of time the position was held. Luckily, Mr. Keller had only one motion picture projector which meant that reels had to be changed and the light would come on resulting in our hands hastily hauled back to our own side of the row.

Photo courtesy of the Laurel Historical Society

Worst of all when the picture (often an Art Accord western) was ended boys and girls parted and wended their ways homeward. Later we did have real dates whereby we could visit the lass in her home as long as the place was well lighted, and we were out of there by nine or ten o’clock at the latest.

Mr. Keller, by the way, lived some distance from the movie house. His home was painted—at least on the outside—with horrific yellows and greens and the entire lot was fenced in with about eight feet of chicken wire.

When he took the night’s receipts home, he walked in the middle of the street and carried a protective pistol in his right hand to ward off highwaymen. As I remember, we didn’t have any highwaymen in Bridgeville back in those halcyon days.

Around the corner from the theatre and further east on Market Street was a mecca for those of us attending the old Bridgeville school (both elementary and high) which was located on Walnut Street.

Maggie Hewes sold every conceivable kind of delectable for us school kids. I was particularly partial to the salted peanuts and penny candies. Her store was also loaded with merchandise to attract the eye of the young. Toys and novelties were there among other wares. Also, I remember I bought my Aunt Nellie a pair of scissors as a Christmas present. Appreciated they were, but for a dollar I bet they would have been hard put to cut hot butter.

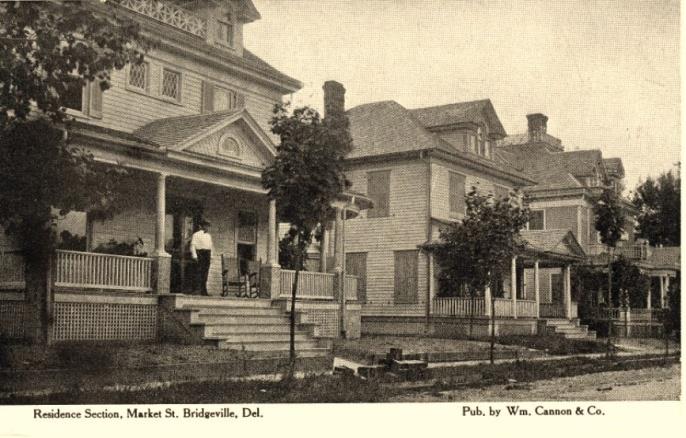

Wandering on eastward on Market Street, one passed the homes of Harley Records, Sol Kline and others, including the house that my mother lived in when she was in her early teens.

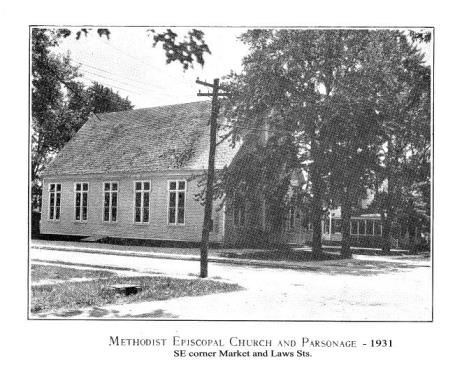

On the next corner was the Union Methodist Church where I was confirmed as a Christian—probably more than once, as I was religious in those bygone days.

Residences took much of the next block except for a two story frame building which was a hotel of sorts.  Then came the stone and brick Willey home at the next corner. That home remains along with a number of other buildings mentioned in this report. I remember Fred Willey played a great game of football for Bridgeville High School. He was a linesman and plenty tough. In modern days, he would definitely have won a scholarship (athletic, of course) to a football conscious university. Joe, his brother, was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad.

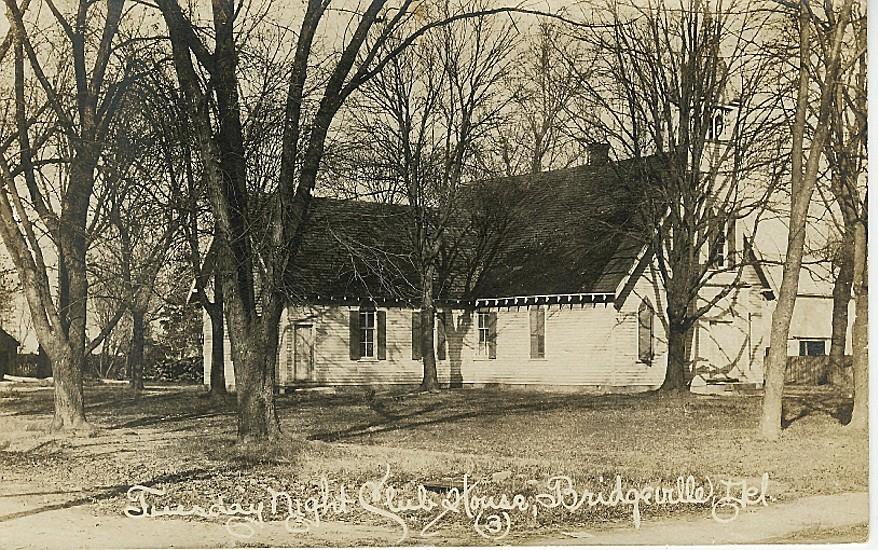

Then came the stone and brick Willey home at the next corner. That home remains along with a number of other buildings mentioned in this report. I remember Fred Willey played a great game of football for Bridgeville High School. He was a linesman and plenty tough. In modern days, he would definitely have won a scholarship (athletic, of course) to a football conscious university. Joe, his brother, was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad.  The first Bridgeville Volunteer Fireman’s operations were carried on in a building property adjoining the Willeys on a side street.

The first Bridgeville Volunteer Fireman’s operations were carried on in a building property adjoining the Willeys on a side street.

Our trek continues eastward on Market Street where we encounter Harry Ake’s original Bridgeville residence.

Photo courtesy of the Laurel Historical Society

Then came another retail shopping area with Norman Scott’s Men’s Store followed by Jim Sullivan’s ice cream parlor, later to become the Sweet Shop overseen by Mayor Culver’s father and behind the soda fountain an old flame of this writer’s served up luscious sundaes and other great concoctions of ice cream, syrup and soda water.

At the corner of Market and Main was the drug store and soda lounge (as differentiated from today’s cocktail lounges) run by Mr. Zott. Edna Zott, his daughter, was one of the prettiest of the local belles. She was one whom I admired from afar as I never dated her, much to my later regret.

Now we cross Market Street and head back westward.

Photo courtesy of the Laurel Historical Society

On the corner, as today, was Hoch’s Garage where my Uncle Norman purchased his Ford cars. At one time, my uncle and Will Swain sold Hudson Automobiles. They had blue bodies and red wheels. (The cars, not the dealers.) That was an unlikely partnership, for, at the time, Mr. Swain was county chairman of the Republican Party and my good uncle chaired the Democrat county executive committee.

Returning westward on the north side of Market street we arrive at Will Cannon’s Hardware Store neighbored by a store run by Mark Welch, and Sudler’s Drug Store.

Across an alley-like thoroughfare was a rather large building housing Sholl’s shoe repair shop operated by an enterprising black man who garnered all the shoe repair business in the area. Then, in the same building was King and Layton’s Department Store which handled goods similar to Sol Kline’s and did a great business with localities as well as those coming into town to do their dealin’. I recall one time that my grandmother traded three dozen eggs for a pair of shoes which my grandfather felt had been too high priced.

Over the shoe repair operation and the K& L store was Lee Short’s Opera House where, like Keller’s, movies were shown sporadically. I remember when The Phantom of the Opera was shown. Bob Jones, a schoolmate and later bigwig with Montgomery Insurance in Wilmington, screamed when Lon Chaney first showed his ugly face.

High school plays were also put on at the Opera House as were various Junior and Senior Proms. What fun!

An imposing home (take a look at it today and you see yesterday’s fine way of life) stood next to the establishments mentioned above. Well-kept grounds and finely sculptured hedges complemented the white pillared structure. Reese Layton, whose Layton Lumber Co. was one of Bridgeville’s larger industries, resided there with his family. Bob Layton, today a fine surgeon, and at the time an excellent tennis player (he trimmed me consistently,) owned a beautiful convertible. I think it was a Diana. Correct me, if I missed that one.

Neighbors of the Laytons were the Cahalls. Dr. Cahall’s children, Anne (who later became a leader in the academic world) and Lawrence, a University of Virginia tennis player were indeed of the gracious world of the times.

We continue. Next door was the residence of the Harry Layton family. He was proprietor of the hardware store to be described later. Then came the home of William B. Truitt, fruit and vegetable broker and parent of Leroy B. Truitt, president, nowadays, of a local financial institution.

The Bridgeville Library now occupies a building once serving as a church. This property faced across the street to compete with the Union Methodist church mentioned above.

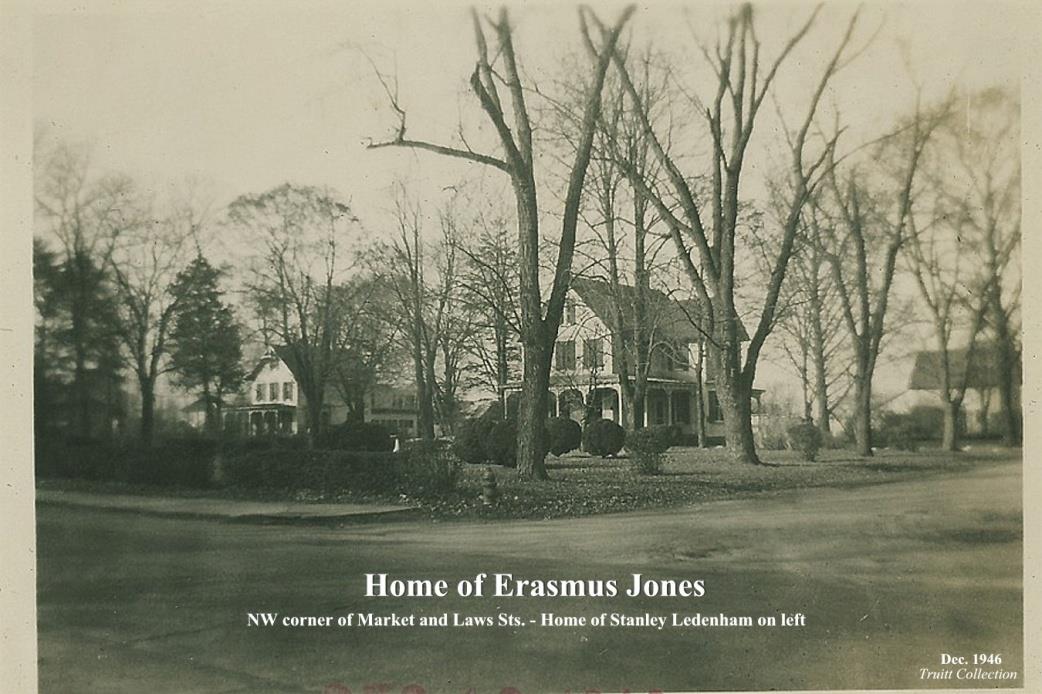

The Ledenham residence occupied a goodly portion of the next block. Mary Ledenham was my teacher of English while I was matriculating at BHS and her brother, Stanley, was associated with the bank, the Baltimore Trust Company, which adjoined the Ledenham property.

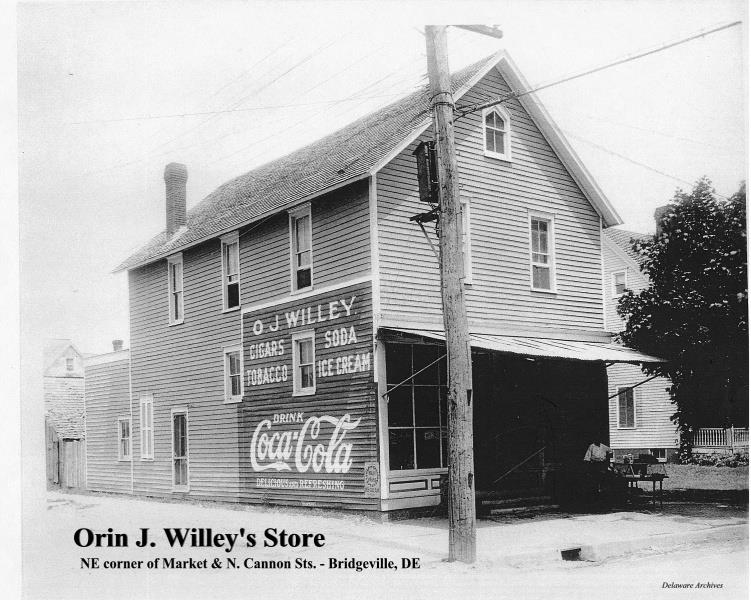

Further down the street, toward the railroad, but a block short of that, was Orin Willey’s ice cream parlor, a lip-smackin’ place if ever there was one!

Adjoining Willey’s emporium was a short tag end of a street stretching northward past Charley Brown’s Garage and a grist mill (behind which was a blacksmith shop.) But it is Brown’s that I want to talk about.

Hoot Brown was an outstanding footballer for BHS. One time he was penalized for wearing leather puttees under his football stockings (which at the time came to the knees.) There was little padding in ball uniforms of those days so Hoot had decided to protect his legs. Unfortunately, the leggings (in some manner) cut the face of an opposing player and complaint led to his having to remove the puttees plus a five yard penalty. I don’t know what the infraction really was. There wasn’t much about unnecessary roughness called in those days of no-holds barred gamesmanship.

Hoot Brown, I believe, was also an auto racer. His car was a souped up Ford (Number 22) which raced around the dirt oval at Harrington (Kent and Sussex County Fair Grounds. Dusty, and acrid with the smell of gasoline and oil, the cars would roar around the half mile track, many times smashing through the whitewashed, rail fence into the infield only to be hauled back on the raceway and continue in the competition.

Bill Brown, raced Number 60, a grey Dusenburg, which won many laurels not only in Delaware but several eastern tracks. I do not recall who rode with Bill, but each racer had a “mechanic” who, seated beside the driver, would “pump” oil as the race progressed.

Although Bill Brown won a number of races, the most famous racing car driver in the general area was Russell Snowberger of Greenwood, who drove in the Indianapolis 500 and wound up in the first ten. Not bad for a little country boy.

Returning to Market Street, we find Kim Wiley’s home and grocery store on the corner and adjacent thereto was (and is) H. C. Layton Hardware Store.

If there is anything that couldn’t be purchased in that emporium (other than food and drugs) I don’t know what it could be. Harness, tools, horse collars, tools of all kinds, work gloves, oil, well you name it—it was there.

One of my favorite Bridgevillians of the bygone era, was Hattie Warrington who wore the smallest ribbon bows ever. She also wore the biggest smile in town. How happy she seemed with the entire world! Her father, Otis Warrington, had a grocery store (and home) neighboring the Layton store. This was probably the most well-lighted store in town and garnered more than its share of the grocery and meat business. Here it was that farmers bartered eggs and other farm products for staples and such. It was indeed a busy place, particularly on Saturday evenings when all came in to town to do their dealin’.

The town constable had a little place of business where one could get a hamburger sandwich (never equaled by modern chain operations) and a cup of coffee that had real authority. It is possible that the original coffee was brewed in the early 1900’s and left to simmer, with added grains and water, in the old agate pot for the next quarter century. Good, though, it was!

In the same building was the local office of the Postal Telegraph Company. Western Union was at the depot.

I skipped past Luther Calhoun’s Barber Shop which was located between Warrington’s and the building housing the telegraph office and hamburger dispensary.

Luther’s shop was unusual in that he gave work to boys home from the University (College in those days) on Saturdays. My cousin Harold, visiting on weekends from Delaware College, was privileged to apply hot towels and lather the faces of those desiring shaves. Other local lads were also given an opportunity to make a little change in that shop.

The recreation facilities (indoor department) of the era were provided by Herb Ryan’s Pool Room. I played there often with Diesty (Slab) Hardesty, my cousin Ralph and others. The game usually was “Keeley” a form of bottle pool. I never got rich from the nickel-and-nickel game, but quite often went into temporary insolvency.

Although the Sunday papers carried comics, there were no comic books as we know them today. However, there were hair-raising novels. Fred Fearnot was a series that I favored and spent a dime each week for the cheap-paper publication. (Today, original copies of the ten-centers will bring hundreds of dollars… I don’t have any.)

The last business house on Market Street before crossing the railroad crossing, was the commission house of William B. Truitt . He was one of the larger operators in the business of buying products from the farmers and shipping such to northern metropolitan markets.

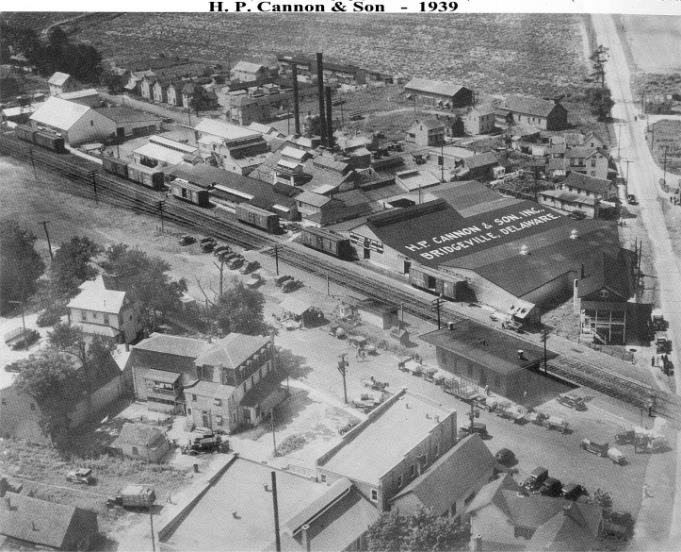

Across the tracks from Truitt’s operations was the sprawling operations of Robert Reese Layton. His factory manufactured baskets, crates, and other wooden containers for farm products as well as manufacturing lumber products and producing construction materials. Extending along the south-bound tracks of the P. R. R. for about a mile or more was (and is) the great canning works of H. P. Cannon & Son.

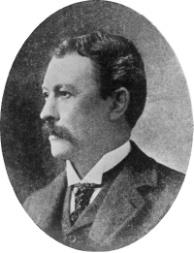

I remember Phil Cannon, tall, white-haired and mustachioed. Seems to me he always wore a cane, dark velvet collared coat and bowler place just so atop his stately head. He was followed in the business by his son, Harry Cannon, member of the Governor’s adjutant staff and philanthropist. He had style; was dapper in dress; yet with a demeanor that brooked respect.

The canning factory contracted with local farmers for various crops, usually before the crop was even planted. This provided an avenue for financing fertilizer, seeds, etc. as the farmer could then go to the bank and borrow money on the basis of the contract with Cannon’s.

I recall that in the early twenties, tomatoes were sold for 25 cents per five-eights basket under such contract. (I bought three tomatoes for about 60 cents just yesterday…and they were on sale!)

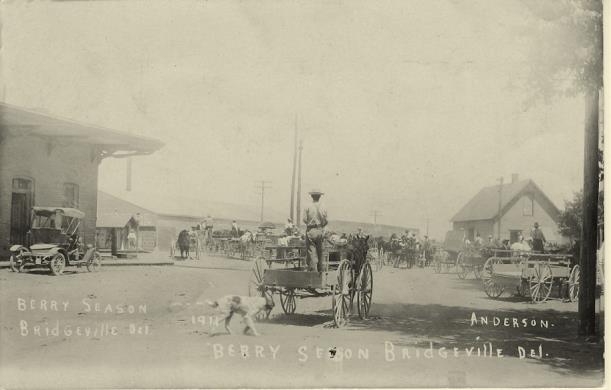

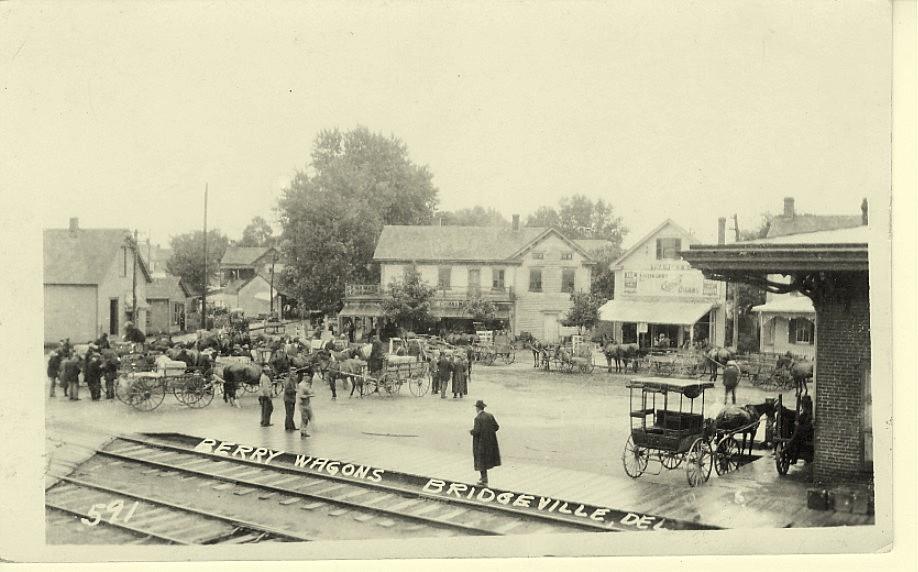

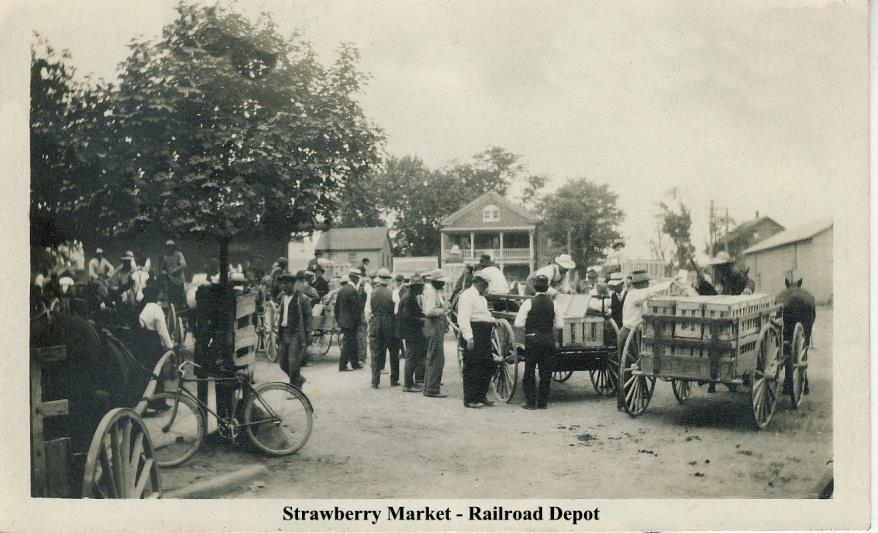

Other products, cantaloupes, strawberries, fruits and other vegetables were usually hauled into town for the commission merchant to buy. Stake wagons, referred to as Dearborns (and pronounced “durbins”, would line up on Railroad Avenue and buyers would bid on the basis of the quality of the products. After an acceptable price (little controlled by the farmer-seller) was agreed upon, the produce would be taken on down to reefer (refrigerator) freight cars assigned to the different buyers. The wagon would be unloaded and that evening the car would be sealed and be sent on its way to the eastern market destination. Later, the railroads lost much of this business due to the flexability of truck movement.

The Bridgeville farm area was basically a truck-farming area. Various vegetables were grown in season along with fruits, particularly apples and peaches, along with some pears.

There was a great rivalry, at the time, between Bridgeville and Selbyville as to which was the “Strawberry Capital of the World.” Both maintained their superiority although I suspect there was not much difference between the volume shipped from the respective towns.

Strawberries were hoed by hand. Also picked by hand. At the time, pickers were paid at the rate of three cents per quart cup. Field hands got house and firewood, vegetables, and ten dollars a week. As wages progressed, the growing of strawberries receded and today this crop is minimal in Sussex County.

Melons, particularly cantaloupes, was another big crop of the time. Women joined in the picking and packing of these great cropes. The crate “makings” (Slats and Crate Ends) were bought at Reese Layton’s factory and nailed together on the farm. Strawberry crates, on the other hand, were bought assembled, and were usually packed with thirty-two quarts of the berries and hauled into town.

Farmers rotated their crops in various fields. I can recall corn, wheat, cantaloupes, cucumbers, tomatoes and pumpkins being grown on our hundred acres just west of town. There was also hay—alfalfa and clover—and, from time to time, peach and apple orchards on the same tract. Those were the days of planting corn in hills rather than in long unromantic rows.

Horse-drawn corn planters were used. Later we’d “thin” it out (no more than three sprouts to a hill.) Conversely, where the corn did not come through, we’d walk across fields replanting, hill by hill. Try that exercise if you’re concerned about your avoirdupois…particularly in front.

Wheat threshing (pronounced “thrashin”) time was wonderful. Farmers pitched in with each other to get the grain under cover before it “sprouted” as a result of wet weather.

First, a grain cutter would go through the fields mowing down the stalks which would be put into “shocks” by field hands following the finder. This latter was so-called because it actually tied the wheat stems into a kind of bougets.

Finally, one morning, usually in June, one would spy the great steam engine complainingly chugging down the lane into the farmyard, followed by neighboring farmers with teams hitched to racked wagons for hauling the sheaves to the thresher (which of course got its motive power from the canopied steamer.) My chore was to haul water to this machine. Pumped at the man-powered iron bucket pump at the barn, water was put into a large barrel which was place on a heave skid (sled) drawn by two mules. Meanwhile farmers were loading wagons in the fields in the fields, hauling the stacked grain-topped straw to the thrasher where the grain, beaten from the sheaves, was bagged, loaded on other wagons and stored in bard and shed lots.

During the morning, the wives of the working men were up at the house preparing the greatest meal of all-time…the wheat threshing dinner.

There were normally two, three, or sometimes four “tables.” This did not mean that there were actually four pieces of furniture. It referred to the number of meal “shifts.” I tried (usually unsuccessfully) to participate in all four meals.

What a sumptuous repast! Ham, chicken, beef, at least four vegetables, yummy gravy, and all kinds of pie. How hungry it makes me, even today, just to think about it!

The entire ritual would be repeated innumerable times in the general area and we all worked, farm to farm. It was hard work, but the comraderie was more than rewarding.

Our patronizing and perhaps, at times, overly paternalistic government would have us believe that we are gradually being poisoned by most everything we eat or drink.

When I look back on how milk was served in days of yore, I wonder how we survived. A cousin and I milked ten cows each morning and night. The warm milk was then brought into the house, strained through cheesecloth and bottle. Bearing in mind that it was still warm (who ever heard of Pasteurization?) We then loaded it into a cart and delivered the cow juice to our in-town customers. Competitors to our business were the Myer Dairy (Delaware Stock Farms) and Sudler’s. Later, about the latter ‘twenties, authorities required cooling and treatment of the milk before delivery.

The Bridgeville educational system of the ‘teens and ‘twenties probably left much to be desired. At the time, the little one-room country schoolhouse was a child’s introduction to the world.

In town was the stone and brick edifice of Bridgeville High School and some of the primary grades. I don’t recall how many were in the school at the time, but I do know the graduating class of 1927 totaled no more than eight. However, in order to graduate, one had to study Latin plus a foreign language. We had a physics and chemistry laboratory. We were inoculated with intensive coursed in English and Math. Thus, I believe those classes prepared us for the outer. True, not most of us did all right in our time. Matter of fact, many of the “improvements” in academe were brought about by our efforts. Many to our regret.

Sports were important to all in those long gone years. From the outside world, we learned about yesterday’s baseball scores through the morning paper which usually arrived about noon. Football, outside of local high school games, didn’t mean too much. Other than the Canton Bulldogs and the Frankford Yellow Jackets, there really wasn’t much to pique the interest.

Occasionally, Delaware College would rate a headline after defeating Lehigh or another small college team. I once say Delaware play Dickinson College at Franklin Field in Philadelphia before Frank Field had its upper deck built. My cousin played for Delaware at the time.

Locally, however, there was much interest in high school sports. Football was a crowd puller for the first couple of years I was at BHS. Hoot Brown, mentioned heretofore, Jeff Gray, Fred Willey were among the great players along with George Ruos, Vic Adams and others. George Ruos coached the team in its last year of play. There were no locker rooms (or gymnasiums in those days) and between halves, the opposing teams would sit down at opposite ends of the field to listen to exhortations from their respective coaches.

Because of the lack of material, both in numbers and quality, Bridgeville abandoned football in the fall and became soccerconscious. The game played in those days was as beset with roughness and injuries as football. Reason we played was because there just weren’t any big boys left in school. I suppose John Lauer was our “giant.”

I got to play baseball for a very good reason. There were only eleven boys in the school. I played at first base and my cousin played third. He and I used to train for the season by throwing a wet tar-taped baseball as hard as we could at each other. My catching hand still tingles from the memory.

Our fans were loyal. All the school girls came out to see us play along with a great number of local townsmen.

For some reason, we never seemed to be able to complete a game with Laurel. It invariable ended in a bit of a fight. Howard E. Hardesty (the original) usually would up in an altercation with a visiting fan. Nobody really got hurt, but there was a great amount of shouting and menacing bat-waving.

Having no gymnasium or locker rooms, players came to the school the afternoon of a game suited up to play and we were permitted to leave classes early in order to be at the ball grounds on time. There was a kind of VIP, egobuilding puffery to be able to get up and march out of class before dismissal time.

The Delaware Stock Farm was situated about a mile north of the western outskirts of Bridgeville on the road to Dublin. The huge barn housed a great number of standard-bred horses and mares that raced at many county fairs throughout the eastern seaboard. Ed Myer, the elder, was a trainer-driver and he had built a half mile oval near the barns where one could see him and other drivers putting the steeds through their paces. His sons later became well-known harness drivers and raced at Grand Circuit tracks with some success.

Well, yes, there were certain disadvantages to the times. Streets, for the most part, were unpaved. Many houses had no indoor plumbing or even electric light. There were few amusements, as we view them today. On the other hand, there was no vandalism (except maybe at Halloween when a few outhouses became upended.) Also, every town had a large sign at its entrance proclaiming “Cut-outs must be Closed and Mufflers Used.” A bit different from today’s show-offs with their tail-raised, widetracked-tired “sports cars” revving it up with loud v-r-r-o-o-m and squealing take-offs and halts at corners.

Except for the open-aired buggies and carriages of days of yore, I think I still like the Bridgeville of a half century ago. How about you, Old Timer?

Mr. Koder M. Collison (1910-1979) was a contributor to the “Seaford Leader”, newspaper writing his memoirs of the Seaford and Bridgeville communities as “The Old Timer.” The article above was taken from the Woodbridge High School newspaper, “The Hallwalkers’ Guide” – January 19, 1976.

The Bridgeville Historical Society has added photographs from the Society’s collection, the Waller Collection of the Laurel Historical Society and Delaware Public Archives to enhance this narrative by Mr. Collison.